Everyone knows vampires don’t exist—until a group of high-level data analysts messing around with some very suspicious math manage to come down with a case of V-syndrome, and Bob Howard has to deal with it. But there’s more to the outbreak than meets the eye, and in the end, Bob and the Laundry will have to face the possibility that something quite nasty indeed has been lurking in its own org charts all along.

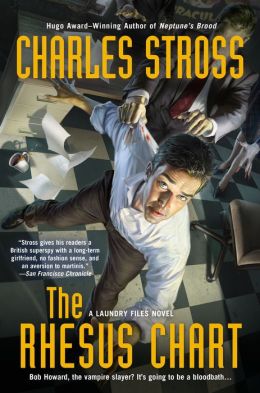

The Rhesus Chart, fifth book in Charles Stross’s Laundry Files series, picks up some time after the events of The Apocalypse Codex (2012, reviewed here) and “Equoid” (2013, reviewed here). I’m always pleased to see a fresh story in this series, and I was particularly interested to see how vampires would fit into the Lovecraftian math-horrors of the Laundry universe—after all, the prologue opens with Mo pointing out all the reasons that traditional “vampires” couldn’t possibly be scientifically viable.

Of course, no one said that vampires have to be the traditional kind. Instead, might the vampire not be a person infected with a similar presence from beyond spacetime to the feeders in the night—except nastier, and with some terrifyingly useful side effects for the host?

Because that, it turns out, is a much more viable alternative to “living entirely on blood.”

The vampire of The Rhesus Chart are, for the most part, of two camps: ancient and terrible or fresh-made and faintly hapless, despite their ruthless business acumen or mathematical chops. The turn, partway through the novel, from “pursuing the Scrum vampires” to “working with the Scrum vampires” is a fun one—cleverly handled, too. Stross manages to shift the narrative focus from hunting down what seem to be adversaries to feeling sympathy for them; this is particularly true of Mhari, who is at first painted as one of those “evil ex” types but becomes a more nuanced and complicated character, one for whom we begin to feel a level of identification.

I liked the twists in focus and identification throughout, as well, while Bob walks the reader through his narrative of the case-file: characters who seem insignificant aren’t, while others change roles quite rapidly, and yet others who were previously background figures develop interesting quirks and depth of personality on the page. Andy and Pete return; Mo is, of course, a relevant figure though she appears less in this book than others; Angleton, too, has his place. As do the Auditors—scary figures all, and for once a solid part of the climactic narrative instead of an off-screen bugbear.

The Apocalypse Codex, as noted in the above review, uprooted Bob from his usual support systems—outside of the Laundry, away from friends and allies, he had to do some sudden and intense personal development. The Rhesus Chart, however, takes a different angle and shows the reader the path that Bob is set to walk down from the inside, exploring the conflicts and dangers of life as a member of External Assets as pertains to on-site incidents. Like the Code Blue, and eventual Code Red, that results from the discovery of V-syndrome—and the fallout from that Code Red, which I found to be rather stunning and sudden. (Without saying too much: the manner in which Stross does the rundown of the conflict that happened out of Bob’s range is an effective combination of detached and achingly personal narrative recreation—not too much “telling” but exactly enough.)

As a whole, this novel is a well-realized bureaucratic horrorshow, a mix of committee meetings and violent altercations, mayhem and minute-recording. Bob’s life as of the end of The Rhesus Chart has changed so drastically and completely from the life he had at the start of The Atrocity Archives that it’s hard to compare the two—as if our protagonist has been two different men. The thing is, we’ve seen it all happen as naturally as the weather changing: as the world grinds into the terrible alignment of the stars and things grow ever more deadly and unstable, each person in the fight will have to undergo drastic evolutions as well. Bob certainly has, and I suspect will continue to.

Which is, as I’ve said before, another reason to love the Laundry Files: it keeps changing, evolving, developing deeper and more complex layers. No danger of episodic staleness, here.

As for The Rhesus Chart: it’s a solid, satisfying entry in the series—well paced, appropriately gruesome, and sharply witty. For those who’ve been reading all along, I feel safe guaranteeing it won’t be disappointing; for new readers, I’d recommend going to the beginning first, and then picking this one up in proper order. The plot is gripping, and the interpersonal subplots are equally so though in a different manner; the closing scene between Bob and Mo certainly left me aching to know what would happen next, where their lives are going to go, thanks to the lethal necessities of CASE NIGHTMARE GREEN. So, overall, I continue to strongly recommend these novels—and to look forward to the next one.

The Rhesus Chart is available now from Ace.

Get Three Tales from the Laundry Files from Tor.com

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.